Previously in this series: 2018, 2019

Of a Literary Persuasion

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen. Okay, you can judge me for not reading this until my 30s. It’s a delight. I see why people turn to Austen not just for psychological insight and juicy plots, but for comfort, too: her writing has a lightness that’s so hard to find. A deft comic touch, a well-earned happy ending – these are rare things. Every year, there are like 17 gorgeous, bleak, midnight-dark drama films, and maybe, if you’re lucky, one decent comedy. But it’s often light stories touch us most deeply.

The Remains of the Day, by Kazuo Ishuguro. 200 pages of a butler philosophizing about what it means to be a Great Butler. But mesmerizing. Ishuguro understands avoidance, denial, the psychological mechanisms by which we protect ourselves. You can feel the narrator’s desperate efforts at self-preservation radiating off the page. I’m filled with dread and empathy, both at once.

The Glass Hotel, by Emily St. John Mandel. An oblique portrait of a Bernie Madoff figure, and the ripple effects of his crime. As in her last book (the post-apocalyptic Station Eleven) Mandel depicts a cinematic, world-changing event, but she’s not so interested in narrating the central story. Instead, she moves around its periphery, giving us characters in various states of doubt and crisis, until the world-changing event moves to the periphery, and these unraveling characters to the center.

Dear Life, by Alice Munro. Lately, I’ve been mulling what makes a great short story, and what makes it different from a novel. Munro’s work is Exhibit A. Her stories pack novelistic twists and depth into just 20 or 30 pages, leaping across time and space en route to abrupt, devastating finales. So maybe that’s the secret to short stories: the agility, the maneuverability. A novel is a cargo ship; you can’t turn 180 degrees without signaling your intentions long beforehand. A short story is a kayak: Munro can lead us down waterfalls and land with a gentle splash.

Circe, by Madeline Miller. Wildly hyped. Worth the hype. The “retelling an ancient myth from the perspective of a relatively minor female character” things has been done, by authors as skillful as Ursula Le Guin (Lavinia), Margaret Atwood (The Penelopiad), and arguably C.S. Lewis (Till We Have Faces, his best adult novel, kind of fits the bill). Still, I think Miller’s sleek, immersive inverted telling of “The Odyssey” may be the best of them all. It glides along like television, but also develops Big Themes in a satisfying way.

Of a Sci-Fi Persuasion

The Killing Moon, by N.K. Jemisin. Apparently Jemisin borrowed a lot of the book’s hierarchical, dream-obsessed culture from ancient Egypt. I’m too dumb to have picked up on that while reading. Instead, it worked for me as a seamless, deeply imagined world. More conventional than the Broken Earth trilogy, but just as tightly woven.

The Dispossessed, by Ursula Le Guin. A scrappy anarchist society ekes out existence on a hardscrabble, barely habitable moon. From there, a brilliant scientist (with a peculiar mix of wisdom and naivete) visits the homeworld. Le Guin is the foremost anthropologist among sci-fi writers, and this is her foremost work of anthropology. It earns the book’s subtitle, “an ambiguous utopia.”

The Eye of the Heron, by Ursula Le Guin. A minor Le Guin work is like a Beatles album track; still better than 99% of stuff by mortal humans. The structure is a little funny, as it veers away from its protagonist midway through, but the left turn serves a structural purpose, widening the reader’s gaze from the traditional axis of “violence vs. nonviolence,” to encompass more feminine (and feminist) perspectives.

The Starry Rift, by James Tiptree, Jr (penname of Alice Sheldon). Though they deal with the pulpy fun of faster-than-light travel and journeys to alien planets, these stories are bittersweet. Some are downright sad. It’s like if Sufjan Stevens did the soundtrack to Star Trek: Voyager.

This Is How You Lose the Time War, by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone. The epistolary love story of two time-traveling assassins. It somehow works both as a lovely fable (bright colors, lyrical prose, storybook structure) and a too-cool-for-school punk sci-fi experience (sly wit, wry futurism, LGBTQ romance). It’s tempting to credit those two disparate strains to the two authors, but I just read Amal El-Mohtar’s Hugo-winning short story Seasons of Glass and Iron, and though singly authored, it braids together the same two styles (with the same success).

Axiomatic, by Greg Egan. Short stories with killer sci-fi premises: a mathematical theory of parallel universes; a rigorous vision of messages sent backward in time; a terrifying spatial anomaly that you can survive only by running into its dark center; a “jewel” implant that allows you to transfer your consciousness from mortal flesh to immortal silicon… Why haven’t lesser writers copied these ideas, making cliches of them? I suspect lesser writers can’t pull them off. Egan writes from deep knowledge and technical expertise; if you lack his skills, you can’t wield his tools.

Of a Wildly Inventive and Basically Unclassifiable Persuasion

The Blind Assassin, by Margaret Atwood. This book has a ridiculous structure. It’s a pulpy sci-fi novel, wrapped in an experimental piece of literary erotica, wrapped in a bleak memoir about aging, decrepitude, and alienation. Who could possibly pull that off?

Interior Chinatown, by Charles Yu. A Chinese-American dude navigates life in a country that refuses to accept him as a protagonist, or even an individual. The whole book is structured as a screenplay: a shapeshifting, impossible-to-film, utterly brilliant screenplay. I love everything Yu has written, from the cerebral self-reflexivity of How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe to the weird and poignant short stories of Sorry Please Thank You, so I’m happy to see this book winning him even wider acclaim.

Someone Who Will Love You in All Your Damaged Glory, by Raphael Bob-Waksberg. Absurd, fantastical short stories about the gritty realities of love. Each story is wildly individual, with its own distinctive voice. The bizarre blend (pathos + tragedy + bizarre comic premises + puns) is pretty much what you’d expect if you’ve seen Bob-Waksberg’s TV show Bojack Horseman, but I was impressed how well he adapted to the new medium.

The 13 1/2 Lives of Captain Bluebear, by Walter Moers. Too silly for proper adults, too long for proper kids, but perfect for weird old improper kids like me. I don’t really get the gender structure of this magical world – around page 500 it occurred to me that, out of dozens of characters we’d met, all but one or two had been male – but I loved the descriptions (and evocative illustrations) of Bluebear’s bizarre fantasy continent. A gentle work of vivid imagination.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bible!, by Jonathan Goldstein. Famous passages from the bible, retold with a light and lovely narrative touch. It makes the old stories feel new again, bringing out their absurdity and (just as central to the book’s purpose) their insight. I smiled a lot.

To Be Or Not To Be, by Ryan North. A choose-your-own-adventure version of Hamlet, with hundreds of different endings. North has a genius for structure, and playing out every funny implication of his premise. My favorite: if you keep choosing the same “path” as the original Hamlet, the narrator eventually steps in to accuse you of making terrible character choice. Not wrong!

Rereading Favorite Authors

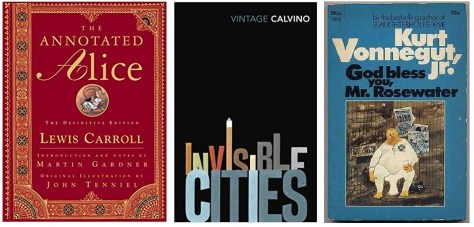

Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll. Much as I love these books, it struck me how plotless and meandering they are. They’re collections of clever scenes, memorable dreamlike exchanges. As such, they face the structural demands of stand-up comedy: you’ve got to land every joke, because one false moment can break the momentum. Through the Looking Glass, lacking the ho-hum scenes with the Mock Turtle, is the better book.

Invisible Cities and Cosmicomics, by Italo Calvino. I enjoy Calvino’s short stories. I enjoy his novels. But his best work lies in between, with these “concept albums” of connected short stories. Invisible Cities weaves together page-long descriptions of fantastical cities; it is perhaps the loveliest book I have ever read. Cosmicomics tells tales of sentient matter and living photons spanning the history of the universe; it is perhaps the coolest, weirdest book I have ever read.

Mother Night, Cat’s Cradle, and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, by Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut espouses a bleak form of hope: he thinks that humans are basically dull, broken, unlovable things, and that we can – and must – love them anyway. Compared to my first reading, I found myself less impressed by the philosophy contained the writing, and much more impressed by the craft. The climax of Cat’s Cradle remains as horrifying and exhilarating as anything I’ve read.

Bonus: Slaughterhouse-Five: The Graphic Novel, by Ryan North and Albert Monteys. One of the best graphic novel adaptations I’ve ever read.

Of a Nonfiction Persuasion

The Chairs Are Where the People Go, by Misha Glouberman and Sheila Heti. Glouberman is an original thinker, the kind of guy who has deeply explored how (and why) to get two dozen strangers to make silly noises together. His friend Heti elicited this book from him, and she kept all the looseness and sloppy phrasing (not in a bad way!) of the kitchen-table telling.

Action vs. Contemplation: Why an Ancient Debate Still Matters, by Jennifer Summit and Blakey Vermeule. A series of cultural probes into the ancient dichotomy between “action” (i.e., doing things in the world) and “contemplation” (i.e., reflecting on the world through philosophy, art, and research). There’s no overriding thesis (and some flux in the definitions of “action” and “contemplation”), but I enjoyed it as a linked collection of essays on contemporary cultural forms (from university syllabi to Pixar movies) tackling these issues of timeless import.

Democracy in One Book or Less, by David Litt. How the mechanics of our democracy have broken, and how to fix them. Written in rich detail and a conversational voice. More here.

The View from Somewhere, by Lewis Raven Wallace. A case against “objectivity” (i.e., the “View from Nowhere”) in journalism. Wallace argues that it is not so much an unattainable ideal as an incoherent one. More than just a theoretical case, he presents concrete alternatives from U.S. history, models of journalism that retain the best of objectivity (i.e., nonpartisanship and a grounding in facts) while ditching the worst (i.e., attempts at “balance”).

Solutions and Other Problems, by Allie Brosh. My own books live in the shadow of Brosh’s. Alongside her storytelling gifts, she has a rare knack for genuinely funny drawings. (I love the faces: embarrassed dogs, angry babies, stubborn adults.) She has also stepped up her game as an artist – the backgrounds and compositions are breathtaking. It’s a long book (at 500+ pages, with 1500+ illustrations, it amounts to a kind of reinvented graphic novel) and a great book: deeper, sadder, more unified, and more expertly crafted than her already-excellent first.

Atlas of Poetic Zoology, by Emmanuelle Pouydebat and Atlas of Poetic Botany, by Francis Halle. I did some work for MIT press, and as in-kind payment, I received these gorgeous books. So much better than cash! Each tells the story of several dozen unique organisms. In lieu of photographs, there are illustrations, and in lieu of dry scientific prose, there are poetic and personal accounts of the creatures. It lends the book an air of magic: like Borges’ bestiary of imaginary creatures, except real.

A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Internet Age, by Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman. A compact and satisfying biography of an important (and very fun) mathematical thinker. The concepts are well-explained and well-contextualized.

The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking), by Katie Mack. A systematic explanation of five ways that the universe might end, each more horrifying and fascinating than the last. Though it’s more buttoned-down than her playful Twitter presence, Mack’s personality still shines through.

Awakenings, by Oliver Sacks. Haunting profiles of patients whose catatonic states were treated with the “miracle” drug L-DOPA. Only one or two case studies are wholly “good” or “bad”; the rest are complex narratives of recovery, adjustment, relapse, and compensation. Some say that no medical writer captured the whole humanity of each person better than Sacks did; I say you can delete the word “medical” from that sentence.

And Finally, Math Books I Blurbed

How to Free Your Inner Mathematician, by Susan D’Agostino. My blurb: “Think of this book as a series of eloquent postcards, sent from a wise and math-loving friend, each depicting a great mathematical idea and inviting you to join in her in the journey.”

Supermath, by Anna Weltman. My blurb: “From the search for aliens to the search for twin primes to the search for racial justice, Anna Weltman spins a lot of great yarns. Better yet, each tale is true: a story of how math serves good or evil, clarity or confusion, depending on the choices of the humans who wield it.”

Mage Merlin’s Unsolved Mathematical Mysteries, by Satyan Devadoss and Matt Harvey. My blurb: “An elegant, charming collection of 16 mathematical jewels: problems so simple they can be explained in a single page, yet so hard they can’t be solved in a single century.”

As always, an interesting list. I followed your previous suggestions by Gleick, and enjoyed (and re-read) The Information the most.

Thank you for sharing!

Thanks, I’m glad they’re useful! I do love Gleick. Was just flipping through The Information again for a few paragraphs I was writing on Shannon.

Thank you for this!

Most of what you say about the Alice books could also be said about Monty Python’s movies, which I think they resemble.

Ah, that’s an interesting point! Maybe not a coincidence; I have to imagine Carroll is one of their many influences.

Between your Goodreads “want to read” stream and this, you’re killing my TBR shelf! And I swore to myself this was going to be the Year of Re-reading.

RIGHT?? He needs to give me a chance to catch up!

I’m glad the list is useful!

And re-reading is good. I always mean to do more! Did a little this year, which is better than most years.

I expected this list to be a short one. To my delight, it was pretty extensive. :). Are these all of the books you’ve read in the year or just a few?

Have you read the Starless Sea? It’s one of my favorites.

I will read a few of the books you’ve mentioned and also, I will make sure to put previously read books in my TBR list. 🙂

I really enjoy your blogs. Thank you.

Thanks for reading! This was something like 2/3 of the books I read last year; I leave off the ones I don’t feel like endorsing. (Compared to the typical year, last year I read fewer books, and included a larger fraction of them. Also, more fiction!)

Haven’t read Starless Sea – will add to my list!