I love wrong ideas. They can be so plausible, so clever, and still… so wrong.

In that vein, one of the best books I’ve read this year is Dispatches From Planet 3, by Marcia Bartusiak. Although it’s not her exclusive focus, Bartusiak explores lots of wrong turns: notions that were superseded, theories that were discarded, and false starts that were forgotten by mainstream science.

I find the tales humbling. They teach us how science really advances: sometimes by inches, sometimes by leaps, yet always clouded by daring and doubt.

I recommend the whole book, but here are five of my favorite moments.

1.

The “Coincidence” of Binary Stars

By the 1700s, astronomers had spotted many binary star systems, in which two stars orbit like pair-bonded swans.

But as Bartusiak relates, they were written off as tricks of the eye:

The common wisdom of the time declared that such stars were actually at various distances from Earth and closely aligned in the sky by chance alone – that it was an illusion that they were connected in any way.

That’s how constellations work, after all. Totally disconnected stars, viewed from our particular spot in the galaxy, happen to look like bears and crabs and whatever a “sagittarius” is. Why shouldn’t binary stars be the same?

This strikes me as a laudable stance. Humans always jump to hasty conclusions, finding meaning in spurious patterns. Shouldn’t we celebrate the astronomers’ skeptical distance, their intellectual restraint?

Sure, they were wrong, but don’t hold that against them!

It took an innovative argument from John Michell to persuade the community. He drew on the new science of statistics, a perfect toolkit for sorting signal from noise, pattern from coincidence. He calculated that for so many pairs of stars to align in such close proximity, the odds were… well, astronomical. The alignment must be real.

2.

The Dance of Planet Classification

Stop me if you’ve heard this one.

(1) A new body is discovered in the solar system, and is hailed in textbooks and the press as a new planet.

(2) It turns out to be kinda small. Other, comparably-sized objects are discovered in its neighborhood.

(3) The planet is demoted.

This isn’t the story of Pluto. Well, it is. But it’s also the story of Ceres, the largest asteroid, and (at one time) the first “planet” discovered since antiquity.

(I like to imagine the pro-Ceres forces mounted a fierce backlash campaign, but scientific expediency won in the end.)

The moral, as I see it: New discoveries re-contextualize old ones. It wasn’t wrong to dub Ceres a planet. But as our picture of the solar system came into tighter focus, it became easier to shift our language, reserving the word “planet” for the big stuff, and developing a new word for Ceres-like objects.

3.

Alien Signals, Alien Noise

In the early 1900s, telescopes revealed dry canyons on Mars. Many folks, excited at the prospect of alien life, took them for canals dug by a civilization.

This was no fringe view. In fact – one of my favorite facts in Bartusiak’s whole book – in 1907, the Wall Street Journal ranked the “evidence” of Martians as the biggest news story of the year.

(Spoilers: they’re not canals.)

Another alien scare came in 1967, when Jocelyn Bell detected the first pulsar. The electromagnetic pulses seemed too fast and regular to be natural. They must be aliens! (Some even dubbed them LGM, for Little Green Men.) But as Bartusiak explains, more pulsars were discovered, allowing Bell to silence the whispers of “alien, alien!”:

It was highly unlikely, she said, that there were “lots of little green men on opposite sides of the universe” using the same frequency to get Earth’s attention.”

The “hey, aliens!” mistake might seem silly. But heck, I found myself tempted to make it last year, with Oumuamua. An object from beyond the solar system, moving right by the sun at vast speeds, with strange and inexplicable dimensions? Sign me up!

Astronomers, of course, were more skeptical. And Bartusiak’s stories show why: the absence of an explanation, exciting though it may be, is not evidence of aliens.

4.

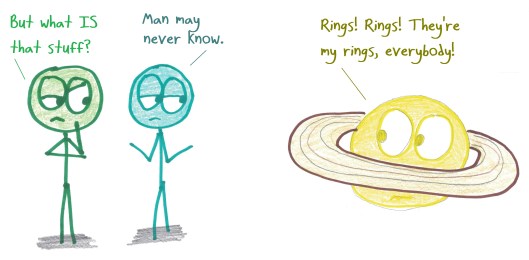

If You Like It, Then You Should Have Put a Ring On It

In his primitive telescope, Galileo became perhaps the first human to glimpse the rings of Saturn. (Right on, Galileo. I hope there’s no bad blood between us after my recent roasting of him.)

But as Bartusiak reveals, he had no idea what the rings were.

“The star of Saturn is not a single star,” he wrote, “but is a composite of three, which almost touch each other.”

That’s what it looked like, anyway.

The true explanation would take generations to develop. Did these bodies touch each other, or not? Was this a single ring, or many? Was each ring a solid object, or a myriad of tiny reflective particles?

I had no idea the question stood unanswered for so long, and attracted the attention of so many name-brand scientists (Huygens, Cassini, Laplace, and Maxwell, to name four).

It goes to show: simple answers do not always come simply.

5.

The First Extrasolar Planet (Wasn’t Real)

I remember the thrill I felt as a kid, reading about the first extrasolar planets, the first hard evidence of other solar systems.

I didn’t know then – in fact, I didn’t know until reading Bartusiak’s book – that in the 1960s, it was widely reported that astronomer Peter van de Kamp had discovered a planet orbiting Barnard’s star. His methods, his evidence, his reasoning – all sound.

But attempts at confirmation failed. Science works like that, sometimes. The discovery, in Bartusiak’s phrase, “disappeared from the history books.”

Luckily, the discovery made it to Bartusiak’s book.

We learn through mistakes. And if you want the deepest, hardest lessons, then you need to learn from the subtlest, most sympathetic mistakes. That’s the joy I got from Bartusiak’s book: to see great wrong ideas of the past, in all their brilliance and beauty.

A very fascinating and interesting read! Thanks for sharing.

(P.S. I thought you might be interested to know that I saw your book in a Barnes & Noble bookstore in Dallas Texas.)

Woohoo, Dallas! GO STARS!!!

One step closer!

On aliens:

From my knowledge of the world I see around me, I think that it is much more likely that the reports of flying saucers are the results of the known irrational characteristics of terrestrial intelligence, rather than the unknown rational efforts of extraterrestrial intelligence.

-Richard Feynman

Haha! “Terrestrial intelligence.” That Feynman!