Sometimes students say precisely what they meant. “I don’t understand the question” means they don’t understand the question. “This is too hard” means it’s really too hard.

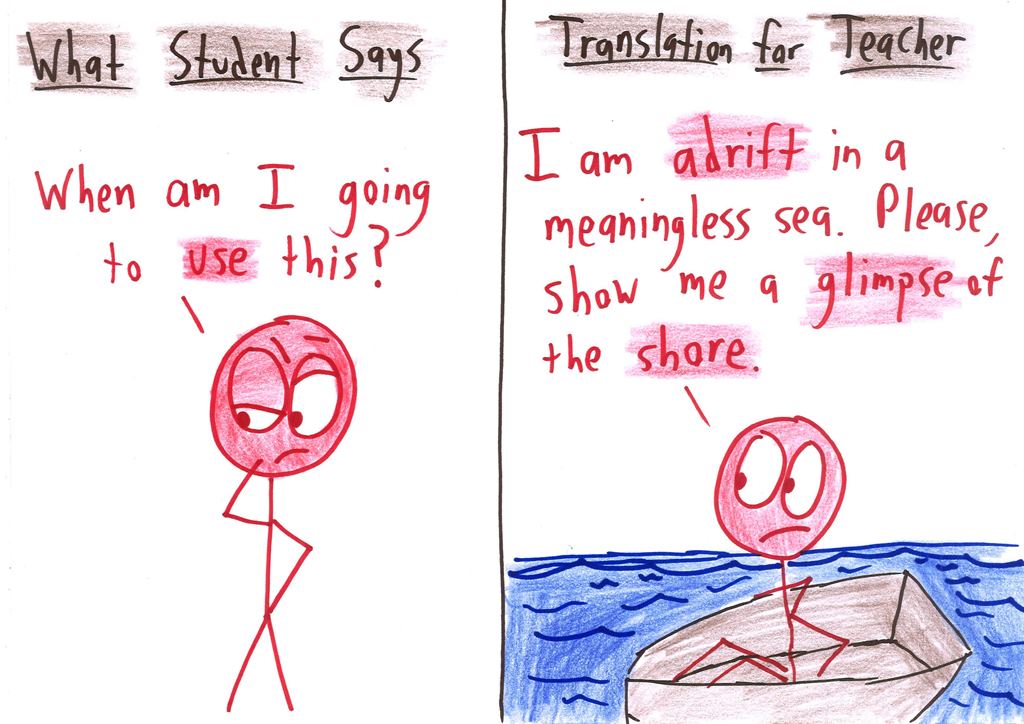

But sometimes, it takes a little translating…

Half of my classroom conversations go like this.

Student: “I don’t get the question.”

Me: [longwinded, exhaustive explanation of what the question is asking]

Student: “Yeah, I knew that. But I don’t get the question.

Me: “Oh. This is one of those conversations.”

Kids may expect to know how to tackle a question upon first glance. Feeling unsure what to do is tantamount to “not getting” the question.

But sometimes, they might know everything they’ll need. All that’s missing is the experience of applying that knowledge, of forging connections between ideas. And that’s not something I should (or can!) tell them how to do.

This is dangerous ground. We math teachers often find ourselves defending the indefensible, trying to argue, “Ah yes, you’re going to need rational functions all the time in your career as… uh…. an HR representative.”

I try to remember that the real battleground isn’t “useful”; it’s “meaningful” or “worthwhile.” If a lesson nourishes our curiosity and makes us feel like masters, then we don’t care so much whether it’ll help us compute our taxes.

Sometimes, the work I assign really is too hard: I’ve misjudged the class’s background, overestimated the impact of yesterday’s lesson, or forgotten about the intricacies of the puzzle at hand.

But sometimes, “too hard” is actually “just right.” The problem isn’t really the problem itself. It’s the human fear of making mistakes, of taking wrong turns. The students don’t need an easier task; they need the courage (and the encouragement) to take risks on this one.

Sure, I’ve been guilty of assigning excessive work.

But far more often, I’ve been guilty of assigning tedious work. Knowing the importance of practice, I forget that not all practice is created equal. Practice that’s folded naturally into a meaningful task is better than a string of decontextualized problems any day of the week.

Some kids really connect with certain subjects, regardless of their scores and grades. Power to ‘em.

For the rest of us, our favorites tend to be the ones where we feel most successful. Earned the top mark in your class? Then that class is likely to earn a special spot in your heart. It feels great to be great.

In this way, grades can actually work against us as teachers, both for their artificial scarcity (“I can’t give all of you A’s!”) and for the sense of hierarchy they engender (“Sure, I got an A-, but my friends all got A’s”).

They create a climate where not everyone can feel successful.

What we need are ways to give kids the chance to feel successful not in comparison to others, but to themselves. It’s no easy task. But it’s the task.

It’s tempting to write off grade-grubbing as groundless whining, like a frivolous and opportunistic lawsuit that any decent judge will chuck out of court.

But for some students, it’s not about the grade itself. It’s about the sense of disconnect: the feeling that the effort they put in was greater than the subjective judgment I’ve rendered.

When that happens, I need to provide channels for their effort. It’s true that some effort bears little fruit. But well-directed effort, almost by definition, will yield success—and it’s my job as a teacher to act as director.

I hate grades with a passion. But if I, however unwillingly, suspend my disbelief in their efficacy, any sentence that has “deserve” rather than “earned” in it regarding grades is highly suspect all around.

Yeah, I wouldn’t say I “hate” grades, but I’d describe them as a very imperfect solution to a very tricky problem, which is society’s need to sort.

From what I understand of the early industrial economy, the main way we used to allocate jobs was nepotism/connections, which is pretty bad. I see our educational system’s concern with grading/ranking students as an attempt to solve this by providing “objective” and “meritocratic” criteria.

It doesn’t always work so great. Other countries (like the UK) put less power in the hands of individual teachers, but that places more burden on big standardized exams, which creates its own problems.

As a teacher, I figure grades are the landscape I need to navigate, however I feel about them. I think subtle distinctions like “deserve” vs. “earned” can be important here – it’s important that grades feel meaningful to students, but I want them to understand the limits of that meaning, too.

I wish all my school teachers thought like you:\

Agreed, absolutely love this post. From a sixth grade pre-al student subscriber.

Thanks for reading, guys; it always surprises me to find out students are reading these teacher-targeted posts, but if the roles were reversed, I guess I’d be curious to hear what students are saying about me to each other, too!

I have really enjoyed math with bad drawings! This hits me at a time when I have been forgetting to try to see it from the student perspective. Thanks for the reminder. (I especially like the one I dont understand the question…).

Reblogged this on Pi UnSquared.

You have students that give you 10 minutes of work?!? I wish I could get that much out of them. Most try to Google answers and write whatever Wikipedia says… Which is never good for math problems.

We had a conversation at our last inservice about grades being more about compliance than actual reflection of knowledge. Not only are students complaining about having to think, but teachers aren’t taking the time to grade or give feedback. Like the student who turns in a paper with one capital letter in the beginning, one period at the end, and lacking organization into paragraph, but gets a 100% on that paper. Or the student who hasn’t come to school since the first day but has a B (82%) in Spanish. But when I go to that teacher’s class and ask for him, she says she doesn’t know him.

There is a time and place for participation grading. But grading on effort is very subjective and usually doeant2 include useful feeeback that students can use to improve.

Indeed – the Wiki-and-regurgitate strategy isn’t good for much of anything!

One lesson I’ve learned from the UK system is the value of less frequent, more meaningful homework assignments. My default in the US was to give an assignment every night. At my school here in England, there’s a homework calendar, and I’m expected to give 1-2 assignments per week.

When students have a few days to do the work, I find the results are a lot better! They have a chance to ask questions, to do the assignment on their own schedule, to come back to it after getting stuck.

I may try something similar when I’m back in the US. Much nicer to receive two thoughtful assignments per week than five slapdash (or plagiarized!) ones.

That’s an interesting strategy. I’ve been using AVID interactive notebooks and the Cornell strategy. Homework every night is to review their notes, write questions they have, and write a summary. I forget the exact reasearch. It’s in my syllabus. But it says that reviewing notes daily raises test scores by 7-10%, which is why I chose this as nightly homework. It should take 10 minutes. I tell them if it’s taking longer than 15 they are doing it wrong and they need to get help from me. About 50% of my students have never done a single homework assignment. It’s not like they’re busy some days and forget. It’s that they just don’t care at all. Actually, 25% of my students are chronically absent.

“Homework every night is to review their notes, write questions they have, and write a summary.” I LOVE this.

“…grades being more about compliance than actual reflection of knowledge.” I used to feel this way quite often. After teaching several years of high school math, I now teach undergraduates. I feel like I’m constantly revising my assessments in an attempt to measure mastery of the student learning outcomes for the course, rather than student effort.

One thing that has helped has been transitioning some of my freshmen classes to a blended format. I use our school’s LMS to create auto-graded quizzes for Fridays. I usually post a video for them to watch and give a short reading assignment. They can then try the problems as many times as they like. Most of my questions are fill-in-the blank; this avoids the scenario where there are a limited number of multiple choice answers and they are just guessing four times until they get a perfect score. I TRY to write questions that they can’t just Google, but I doubt I’m truly successful at this yet.

From the analytics of an average class, I can tell that about 30% of students aren’t watching the videos or trying the problems more than once or twice. So their low grades do reflect low effort AND low mastery. For the other 70%, the quizzes with multiple attempts provide plenty of practice before they have to get it right on an exam.

At the college level, I also have a lot more freedom to choose my category weights in the gradebook. Right now, 40% of their course grade is for proctored exams. I am seriously considering making that 60% next semester. I could have never gotten away with that in high school – I would have had parents beating down my door.

Another strategy that has helped is giving homework requiring students to primarily explain things rather than give numerical answers. For example, “The steps to solve this linear equation are given. Explain which property of real numbers justifies each step.” Or, “Read pgs. 10-20. Explain the concept that was clearest to you. Then tell me which concept was muddiest, and why. Write a good question about it that I can answer in class.” Neither of these questions can be answered by Wikipedia.

It sounds like you’re taking some strong steps to address the things we are working through where I teach. But I have a question/concern.

Are you sure they aren’t watching the videos? Have you considered that maybe they can’t learn from videos? Think about in lecture when someone stops you and says, “I’m really stuck on that that 2/6. Where did that comw from?” And you’re baffled because it seemed so totally obvious! Then you say, “I needed a common denominator so I multiplied this fraction by 2/2.” The lighbulb goes on, a bunch of people kinda murmer “oohhh…” and you move on.

When they watch videos, that can’t happen. If you leave out a detail, their brains get stuck. They can’t complete the learning peocess because there is a gap. They can’t fill it in because there is a video… There’s no person they can question. There’s no person to walk them through a path of logical reasoning.

Personally I’m taking a college Biology class right now. I’ve stopped watching the videos for that reason. I was wasting 6 hours a week studying videos that didn’t fill in my knowledge gaps. They left me with questions I can’t ask. I get the same quiz and tests scores now that I don’t watch the videos as I did when I was giving them all my free time. Why waste my time?

The analytics allow me to see who clicks the video links. For those who do click the link, I have no way of knowing how much of the video they watch. But for those who don’t even click the link, I know they didn’t watch.

Was not at all saying that video learning is the solution or a perfect method. However, I also pair this with a discussion board space. If they don’t understand the video, they can post their questions. I check periodically throughout the day and answer. They can also come visit me during office hours in person if they have a question. And I try to always offer multiple options for learning; for example, a video OR textbook reading OR online tutorial.

The videos are optional; I was trying somewhat uncessfully to say that I see a pattern of low effort. If a student doesn’t watch the video but gets a decent quiz score, that’s fine. Some students are required to take the course but find it easy. Others would rather work with a tutor or work through textbook examples. What I am saying is that students who don’t watch the videos, don’t read the textbook (as evidenced by the fact that they haven’t even purchased it), don’t come to office hours, and don’t attempt quizzes more than once clearly seem to be displaying minimal effort.

I didn’t know you could see if they even watched the video. So you have some data showing correlation between your videos and quiz score. There’s a push here with people and “studies” saying there is no correlation between homework and test scores. But people can’t learn math (or much else) through osmosis. They have to try to think through it and work it out on their own, then have someone to work through their questions with them. Especially when there is information from multiple classes going into the brain all day… They can’t remember everything without every having to work with it later.

I 100% agree with you. 🙂

The problem with grades is that they are relative to a treadmill instead of relative to the ground that the treadmill is sitting on. If we replace grades with levels (think Dungeons and Dragons or myriad computer games), even the dumbest kid in the class can feel some sense of accomplishment.

My son’s school (he is in high school) reports two grades (A-F), side by side, for every class. A recent email from the principal explains this: “The first grade on the report reflects the ‘quality of work’ of the student in the particular subject. This grade indicates the competency level of the student’s work relative to the teacher’s expectations for the class. This would reflect the student’s skill level for a range of assessments such as writing a term paper, conducting a lab or showing evidence of knowledge on a test. The focus of this grade is the quality of the student’s work product. The second grade on the report, the ‘investment in learning’ grade, reflects characteristics such as the student’s commitment, responsibility, effort and participation. This grade represents the student’s disposition towards learning and specifically those qualities which effective learners bring to bear on a subject. I encourage you to look at the two grades side by side. This will give you a sense of the balance between what your child has put in as well as what he or she has produced. The anecdotal comment is meant to clarify or elaborate on the meaning of the two grades. If your child has received an incomplete, he or she must design a plan with us for completing the course requirement.”

Ben, as a professor I’d really like to translate your post and re-publish it in my blog in Spanish (obviously linking to the original post.) I was wondering if you’d allow me…

Sure – thanks for asking!

Thanks! I’ll let you know when it is done.

A very interesting set of thoughs, as usual. Ben: I’m Pedro Ramos, from Spain, and I’m blogging about education in Spanish. I would really like to see your ideas traslated to Spanish, in order to make them available to the Spanish community (unfortunately, a big part of it is not good enough with English). If you are interested on that, please contact me. Perhaps using twitter, I’m already following you. My twitter: @MsIdeasMnosCtas

Your perspective is something I can agree upon. If only all my teachers thought like you!

Usually when I say “I don’t understand the question.” I mean, “what formula should I use?”.

These are Awesome! Thanks Ben 🙂