One piece of classroom tech has always vexed and fascinated me. It’s my magic wand, my Batmobile, the love of my teaching life.

I’m a whiteboard man.

My romance with the whiteboard began with embarrassment and miscommunication. (It’s just like any rom-com movie plot, in that way.) You might think it’s hard to screw up a whiteboard; you’d be wrong. I spent months scraping half-dry markers against the shiny surface, too stubborn to admit I was writing in invisible ink. Students in the third row squinted at my writing like it was a high-stakes eye exam.

When my marker supply ran out mid-period, I’d send a student to the front office to plead for reinforcements. (Somehow I hadn’t learned to carry a spare in my pocket.) “Make sure it’s a good one,” I’d urge, but my emissary never returned with a nice black Expo like I’d hoped. Invariably I got a smelly knock-off in an impossible color like periwinkle or infrared.

I’d sigh. My student would shrug. And I’d soldier through the lesson, with the class gagging at the marker’s off-brand stench.

Even with a trusty Expo in hand, I found ways to torpedo my own lessons. Too often I insisted on filling the board to the very bottom, knowing full well that this was an idiot’s errand. “Can you guys read this?” I’d ask my geometry class, stooping to scribble three inches above the bottom edge.

“Kind of,” says one kid in the front.

“No,” says everyone else. “Not even a little.”

“Well, I’ll just finish this one point, since it fits down here,” I say. “But I’ll read it aloud, so you guys know what it says.”

“Wow, a real genius at work,” I now picture the kids muttering. “That’s exactly what whiteboards are for—to write things that only the teacher can see. Then you can just dictate to us like we’re courtroom stenographers. If there’s one thing we 14-year-olds excel at, it’s purely auditory processing.”

I still hadn’t figured out what that big white slab at the front of the room was good for.

My breakthrough came teaching solids of rotation—the culminating topic of AP Calculus, and thus the sworn enemy of AP Calculus students. The idea is to take a flat 2D region, and rotate it around an axis, like a flag spinning around its pole. If you look at all the points it passes through, you get a solid 3D shape—the spinning flag, for example, would form a wide disk-like cylinder.

Finding the volumes of these solids can be an exercise of maddening complexity. As I rose to the board to trudge through our first example, I decided to throw my plans to the winds. “No computations today, guys,” I said. “Today, we’re just drawing pictures.”

For the next 45-minutes, scarcely a single word tarnished the board. Instead, our discussion orbited around the shapes emerging slowly upon it. What if we rotate around a horizontal line? What about a vertical line, or a diagonal line? What if the 2D shape looks like this, or like that, or like two of these put together? What if, what if, what if?

“Damn, Orlin, you can draw,” said Gilberto, a sentence I’ve never heard before or since. The students mimicked my motions in their notebooks, checking their neighbors’ work. They were learning not just what the shapes look like, but how to conceive of them, how to persuade the 2D canvases of their thoughts that these were real solids, objects with true depth. That day, the whiteboard didn’t just show, as a projector does. It taught how to see.

Experiments in color came next. One day, soldiering through a long example, I realized that one color is too few—monochromatic streams of text will sing kids right to sleep.

So I tried attacking with a whole armada of colors, but that backfired. The board became a splashy muddle of distracting contrasts, proving that even the YouTube generation can get overstimulated.

Later, I was laying out vocab terms in biology, alternating mindlessly between red and black, when a better path suddenly appeared. I decided to put the terms in red, and the definitions in black. “Ooh, that’s so much better!” Stephany said, laughing.

I started seeing the whiteboard as a rainbow-board.

Weeks later, I was whipping my Trig class with the hardest proof of the year. An equation stretched across the entire board, and we were chasing after terms, tracking six variables. “Wait, what happened to the xa2 on that side?” Nelly asked. Crap. If I’d lost Nelly, I knew the rest of the class was doomed.

“Here,” I said. “Let me try to clarify.”

I went back and rewrote all the xa’s and ya’s in red, the xb’s and yb’s in blue, and the xc’s and yc’s in green. Suddenly, from the black-ink haystack of coefficients and function names, the needles we were seeking leapt into view. “Oh!” said Nelly. “I get it.”

Color is magic. The blackboard is Kansas, and the whiteboard is Oz.

The better I got at teaching, the more creative I grew with the whiteboard. Or maybe it’s the other way around: the greater my mastery of the whiteboard, the more my teaching benefited.

I discovered the beauty of diagrams and schematics. Why write plain text, line by line, treating the whiteboard as a wall-sized word processor? I started working in more charts, pictures, and side-by-side comparisons.

Since I was creating on the spot rather than projecting pre-made slides, I was flexible to follow student suggestions and chase tangents. “You’re asking why the economy crashed?” I said one day. “Well, let’s suppose Janet wants to buy a house, and James works for Goldman Sachs…” I started sketching relationships on the board, utterly derailing my lesson plans. The class drank it up.

One day, introducing the psychology of vision, I announced, “We’ll be passing around a marker. When you get it, come up to the board and write down something you’re curious about. Then pass it on to someone else.” Ten minutes later, the board was a handwritten collage of questions ranging from the thoughtful (“Why are some people colorblind?”) to the stone-cold brilliant (“What makes dogs ugly?”).

Years later, I’m still exploring the many-sided personality of that one-sided tool.

My point is not that the whiteboard suffices for all purposes. It doesn’t. (I often nagged colleagues to borrow their digital projectors.) My point is that, in our haste to adopt new technologies, we risk making the same mistake as the Incas, who invented the wheel but used it only for children’s toys. What’s the point in harnessing a powerful technology, if you’ve got no idea how to employ it? Why give me the controls to a space shuttle, if you’re going to replace the interface before I even learn how to steer?

Teachers need time to master their tools. Ours is an applied science, a practical and dynamic art of responding to students’ needs. Good technologies can help, but only experience will reveal how.

Though I’m an old-school soul—a whiteboard man—I’ve grown to appreciate the new technological landscape. After eight happy years with my keyboard-less flip phone, I’m finally upgrading to a smartphone. (“He’s been with that phone longer than he’s been with me,” my wife will no longer be able to say.) Still, with this blog as my witness and my tribute, I’ll always be grateful for the power and flexibility of the humble whiteboard.

i prefer the blackboard.

Classier, but messier.

Sames

You are silly a blackboard is so rubbish

good stuff Ben, blogs like yours and the ideas therein are a big part of what makes the internet so fun and educational. I agree with the color-coding, never did it as a student but have realized its value as a teacher.

Yeah, I had a great bio teacher who loved using different colors. It didn’t make much difference for me; only after becoming a teacher did I really get what she was doing.

what are your preferred whiteboard markers btw? is it Expo all day every day?

Never had good luck with other brands. Open to suggestions, but Expo is the reigning champ.

Great post! (and I’m not even a teacher… oh, wait, TA next quarter of grad school)

Good luck! I TA’ed once in college. It’s pretty fun if you’ve got a good group and a good professor.

Big fan of everything you said here. I LOVE the whiteboard…even more than the SmartBoard, and so do the kids.

I went through a similar thing where the kids got lost in one color and then I erased and made it multi-colored, resulting in a lot more success. Best thing it helps with for me is organizing like terms…

…although 6x^2 + 6x^2 is still 12x^4 — I’m not sure if you knew that.

Oh, sure. Also, to quote a friend’s colleague at an elementary school: “2^3 is just another way of writing 2*3.”

I agree, whiteboards are truly amazing. They are the best when working on group projects because you can color code opinions and thought by person/categories. Whoever made whiteboards was a brilliant individual!

Apparently either “Martin Heit, a photographer and Korean war veteran” or “Albert Stallion, while working at American steel producer Alliance in the 1960s.” Either way, big kudos.

Wow, I would agree, the biggest surprise I had with w/b’s my first year was I thought kids would find them childish, but I found that they loved them. I then began to use them in a variety of ways which made me smile as I read this piece.

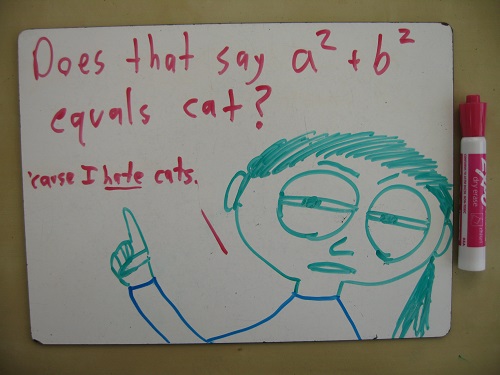

Glad to hear they enjoyed whiteboards too! It’s also fun in math class if every kid has a little whiteboard, like those little personal chalkboards in old-school classrooms. (If you can persuade them not to write each other obscene notes during class, anyway.)

My brother made a hand-held whiteboard at a ceramics workshop! We use it all the time when talking about math!

Do you weirdo mean maths

Whiteboards are the wrong size. Most classroom boards are the size of blackboards, which were made on plywood, and so were 4×8 feet. The only reason for the bottom third of a black board is so that a first grader can write on the board.

The optimum size for a whiteboard is about 30″ tall, and runs from about 8″ below shoulder height to whatever above. And you want multiple boards.

One school where I taught math, when we got to the graphing component, I took the time and used permanent marker to make a permanent 3×3 foot chunk of graph ‘paper’ on the board. It wasn’t really permanent, as the solvent in the pens attacks it, and once a week I’d have to redo bits of it.

One company I worked at had a ‘brainstorm room’ Whiteboards floor to ceiling all 4 walls. When a worker had to bring a kid to work for some reason, they’d give her a bunch of markers and let her ‘decorate’ the bottom half of the room.

I need a new whiteboard has anyone got one if you have what is your email address

I really like using whiteboards while teaching. They are new and can be used to keep students interested in learning. I like how you included pictures of your usage of different colors on your whiteboard. I think using different markets is a good way to catch your student’s attention while teaching a new principle.

Colour is also be possible with a chalk-board, but coloured chalk was less widely available. Cleaning chalk was also messier (although there were good cleaning aids for that).

Choosing how to partition by colour is the fun part; should all the x co-ordinates be one colour and the y co-ordinates another ? Or should each of the vectors under discussion be one colour ? Of course, the answer depends on the problem described. Colour lets you make certain associations stand out; the trick is to pick which associations it’s most valuable to make stand out.

The ability to improvise is precious. Slide-shows are hard to edit, especially in real-time while displaying them, so end up being a strait-jacket for a presentation.

Back when the company I was then working for was preparing to switch to git (a version control system programmers use), my friend Johan had used me as reviewer for the slides he’d prepared for talk he was going to give, helping colleagues understand how the system works. When we actually got to the room, the projector wouldn’t listen to his lap-top, so he couldn’t show the slides to the audience. I duly (since I knew the slides) took to the white-board and served as his “slide-projector”, drawing the diagrams as we went along, animating intelligently as he spoke. Our audience found it more engaging, we had more fun and I think we got the story across way more clearly than any prepared slides could have done.

Of course, you can’t usually afford to have a senior colleague serve as your real-time illustrator, but if you can learn to animate your story while you speak, you’re clearly onto a winning strategy.

good